About This Location

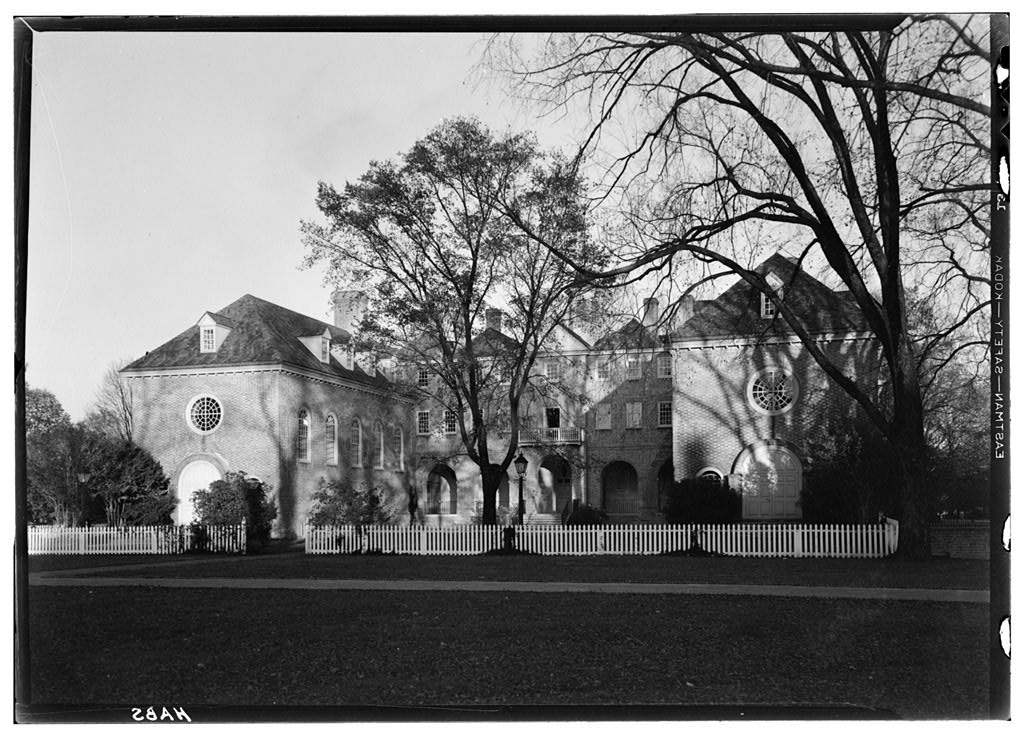

The first public institution in British North America devoted solely to the care and treatment of the mentally ill. The original building was destroyed by fire in 1885.

The Ghost Story

The Public Hospital of 1773 stands as America's first institution dedicated solely to the care and treatment of the mentally ill—and its dark history has left an indelible mark on the spectral landscape of Colonial Williamsburg. Proposed to the Virginia House of Burgesses by Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier in 1766, the hospital admitted its first patient on October 12, 1773. What began as an enlightened attempt to treat mental illness would become a monument to medical cruelty.

Designed by Philadelphia architect Robert Smith, the brick building contained 24 rudimentary cells, each equipped with barred windows, reinforced doors, straw-filled mattresses, chamber pots, and iron shackles attached to the walls. In 1799, two dungeon-like cells were constructed beneath the first floor for patients prone to "raving phrenzy." The prevailing 18th-century belief held that mental illness was a chosen state—and the "cures" reflected this cruel philosophy.

Patients endured ice baths designed to shock them into lucidity, bloodletting with lancers and scarificators, and the infamous tranquilizing chair invented by Dr. Benjamin Rush. This terrifying device restrained patients completely while depriving them of sight and restricting blood flow to the brain. Rush believed "Terror acts powerfully upon the body, through the medium of the mind, and should be employed in the cure of madness." Patients were immobilized in these chairs for days or weeks, sometimes dying from the treatment itself.

The hospital's most compassionate era came in 1841 when Dr. John Minson Galt II became superintendent. He introduced Moral Treatment practices, viewing patients as deserving dignity rather than punishment. He decreased the use of restraints, provided talk therapy, and advocated for community-based care decades before his time. For twenty-one years, he nurtured a therapeutic community within the asylum's walls.

Then came the Civil War. On May 6, 1862, Union troops captured Williamsburg and the hospital. When soldiers arrived, they found 252 patients locked in without food or supplies—abandoned by fleeing white staff. The humanitarian community Dr. Galt had built was destroyed overnight. Devastated and suffering from depression, Dr. Galt overdosed on laudanum two weeks later, on May 17 or 18, 1862. The massive dose caused blood vessels in his brain to burst, and he was found dead in a pool of blood in his home on the hospital grounds.

On June 7, 1885, an electrical fire swept through the original building. The nearest fire engine was in Richmond, fifty miles away. Students from the College of William and Mary rushed to help, but the blaze claimed the original 1773 structure and five other buildings. Two patients perished, and 224 were displaced. Those who survived were transferred to a new facility at Dunbar Farms, where Eastern State Hospital operates to this day.

In 1985, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation reconstructed the original hospital on its excavated foundations, funded by a million donation from DeWitt and Lila Wallace of Reader's Digest. The reconstruction opened as a museum depicting the evolution of mental health treatment. But the spirits of those who suffered here never left.

Dr. John Minson Galt II remains the hospital's most prominent ghost. After his former home was demolished, locals believed his spirit simply moved to the neighboring asylum. The Lee family, who occupied his house after his death, reported that his bloodstain on the floorboards could not be removed despite constant scrubbing. When they replaced the stained wood, Mrs. Lee was shocked to find the stain had reappeared on the new flooring the next morning. Her children woke her nightly, claiming "a man is in the upstairs room where Doctor Galt died."

Today, staff report Dr. Galt's spirit making rounds through the reconstructed facility. A maintenance worker vehemently claimed to have seen "the shadow of a wheelchair" moving through empty corridors. Muffled voices and knocking on walls occur regularly, especially in evenings and on weekends.

A male patient who spent twenty years chained to a wall still haunts the hospital. Visitors hear the unmistakable sound of dragging chains echoing through the halls, growing louder when approached. He appears as an emaciated figure, his wrists and ankles bearing eternal wounds from his restraints. The cells still exist in spectral form, with phantom patients rattling invisible chains.

Employee Amy Billings reports: "Tourists complain of sudden gusts of wind sweeping through the halls. What's even more strange is sometimes when we arrive in the mornings, the bed in the exhibition room looks as if it's been slept in."

Another Colonial Williamsburg employee, Cindy Franklin, experienced the playful side of the haunting: "At times, items in the hospital seem to disappear. No matter how long we search, we can never find them. The weird thing about this is later the same day they magically reappear. Sometimes I think our ghost is a practical joker. Maybe he's bored and needs to get into a little mischief."

Visitors to the reconstructed cells report experiencing sudden claustrophobia, panic attacks, and the sensation of being chained. Some claim to see the cells as they once were—filthy, dark, and occupied by suffering spirits. Photography in these areas often reveals figures that were not visible to the naked eye.

The reconstructed Public Hospital closed to interior tours in September 2022, but visitors can still walk the grounds where countless souls suffered and died. The spirits of patients subjected to ice baths, bloodletting, and the tranquilizing chair remain locked in perpetual torment. Their screams, once heard throughout Colonial Williamsburg, now echo only in the memories of those sensitive enough to hear them.

Researched from 10 verified sources including historical records, local archives, and paranormal research organizations. Learn about our research process.